In The Umpire Strikes Back, the late Ron Luciano told how much

he liked having Ellie behind the plate.

He

was a buffer between the perennially feuding Luciano and Earl Weaver,

had "the nicest way of arguing of anyone in baseball," and was even

trusted to call balls and strikes if the ump was "having a bad day."

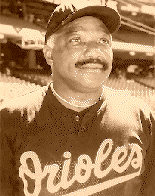

Perhaps no Virgin Islander has made a greater

lifetime

contribution to baseball than Ellie Hendricks. He has worn the

Baltimore Orioles uniform for far more games than anybody else -- his

major-league career spanned 12 seasons, and he is heading into his 24th

year as the O’s bullpen coach. In addition, he played in 16 Puerto

Rican winter seasons and earned the nickname "The Babe Ruth of Mexico"

during four years there.

Perhaps no Virgin Islander has made a greater

lifetime

contribution to baseball than Ellie Hendricks. He has worn the

Baltimore Orioles uniform for far more games than anybody else -- his

major-league career spanned 12 seasons, and he is heading into his 24th

year as the O’s bullpen coach. In addition, he played in 16 Puerto

Rican winter seasons and earned the nickname "The Babe Ruth of Mexico"

during four years there.

Hendricks was born in Charlotte Amalie in 1940. He did not come to baseball until age 13 because of a childhood accident that broke his feet.1 "I was introduced by my uncle, Wilburn Smith, who at the time was one of the star players, shortstop, second base. He was well established in the islands." Ellie played in the local men’s league, thanks to his uncle and that mainstay of St. Thomas baseball, Lealdo Victoria (who passed away in 1998). "Lealdo and I became very, very close friends--he was more of a father figure to me. The Texaco Stars were a club, you had to be a member. They ushered me in and nurtured me. It was probably the best thing that happened, because I matured fast and I learned the game playing with those guys."

Four years later, the 17-year-old Hendricks signed to play pro ball. No less a figure than Hank Aaron was instrumental. "Hank came down on a tour after the 1958 World Series, a hitting exhibition. Bill Steinecke, who was then a scout/manager in the Braves minor-league system, him and Luis Olmo, they all came with Hank. On Friday afternoon, I was asked by my principal, would I be willing to go catch the exhibition? I said ‘When!?’"

"There was supposed to be a clinic that Saturday, and I didn’t go because I had my chores to do around the house. That Sunday, I knew there were two games, it was in all the papers. But since I did not go to the clinic, I decided I was not going to go to the games. But I went to church that morning, and after church I went out to the ballgame, just to see it, because it was against St. Croix, sort of an all-star thing. And while I was there, Hank saw me sitting in the stands."

"Everyone in the stands was asking ‘Why aren’t you down there?’ because Hank was a big name. We were not used to seeing major-leaguers, professionals for that matter, spending time with us. So he saw me and said ‘Why aren’t you out here?’ and I told him ‘I didn’t go to the workout yesterday, so it’s not fair to the guys who went and were chosen.’ He said ‘Well, I want you. So go and get your uniform. It’s across the street [with Ellie’s grandmother, who lived right by Lionel Roberts Stadium]. I read about that!’"

"So I put on my uniform, and still sat in the stands. In the seventh inning, we had the bases loaded, and Mr. Steinecke called me in to pinch-hit for my cousin, Gene Francis, and he was leading the league in hitting! But as fate would have it, I hit a double and drove in three runs. After the game, they asked me to sign a contract. I said ‘I couldn’t, my mom’ll kill me,’ but my uncle said, ‘Go ahead, I’ll sign for you.’"

At McCook, Nebraska in 1959, Ellie had a dismaying early experience--his first exposure to the knuckleball, courtesy of 20-year-old Phil Niekro. "Oh God, yes. Poor Knucksie, he held his heart, he was more worried about me than I was about myself. I had a brand-new catcher’s mitt, the first one I ever owned, and I was there trying to break it in. I just tried to keep the ball in front of me, but it was bouncing off every part of my body." Manager Bill Steinecke had to come for him in the sixth inning.

Also on that squad was future author Pat Jordan, who may have captured the flavor of minor-league life and disillusionment better than anyone in A False Spring. Jordan's vignettes of the profane yet endearing "Steiny" are especially humorous; the "very black, very limber" Elrod, who "spoke a rhythmic calypso English that amused most of the American players," has a run-in with the bonus baby (but the smile never leaves his face).

The Braves released Hendricks in December 1960, but the Puerto Rican league became his safety valve during his career's bleakest period. Ellie did not play summer ball in 1961, working at a car rental in St. Thomas instead. However, Luis Olmo, a teammate of Alfonso Gerard’s with Santurce, was managing the Cangrejeros when Ellie first turned pro. Olmo offered an invitation, and his successor, Vern Benson, wanted to get a longer look. Benson was also a coach with Cardinals farm club Tulsa, and the organization needed catchers.

Hendricks

backed up Valmy Thomas and then

shared the job with him during the next two seasons. "When I joined

Santurce, it was good to see someone from home. Valmy may not know how

much he helped me as a player. I would ask him certain things about

catching, and he would never answer me, but I watched him and I learned

from him. At first I thought, maybe it’s that St. Croix–St. Thomas

rivalry, maybe you don’t want to talk to me! But invariably, he would

do something and he would look over my way, as if to say ‘I hope you

got that.’"

Hendricks

backed up Valmy Thomas and then

shared the job with him during the next two seasons. "When I joined

Santurce, it was good to see someone from home. Valmy may not know how

much he helped me as a player. I would ask him certain things about

catching, and he would never answer me, but I watched him and I learned

from him. At first I thought, maybe it’s that St. Croix–St. Thomas

rivalry, maybe you don’t want to talk to me! But invariably, he would

do something and he would look over my way, as if to say ‘I hope you

got that.’"

Ellie roomed for a couple of winters with Horace Clarke at the San Juan YMCA, until Clarke was traded from the Senadores to Ponce.2 "There was that rivalry with St. Croix, I even had people asking me ‘How can you room with him, you’re a traitor!’ I said, ‘Hey, he’s a nice guy, I played against him in high school.’" Although they were rarely around at the same time, owing to the schedule, they still became close. Hendricks remembers Horace, "who hardly said anything," playing his vibes and also a xylophone.

He also recalls the generosity of another Alomar brother, Tony, and Juan "Terín" Pizarro. "They took me under their wings, drove me anywhere I wanted to go, wouldn’t let me spend my money. Pizarro and I to this day remain good friends." Ellie learned more craft from catching Terín and Rubén Gómez, and cagey vets like Canena Márquez and Ozzie Virgil also taught him a trick or two. "They would look terrible swinging at a breaking ball early in the game and then look back at me. When I got in a tight situation, I’d call for that breaking ball and they would rifle it to right-center, and when they got to second, they would look back at me again. Pizarro would say ‘You big dummy, don’t you know they’re good breaking-ball hitters who can’t catch up to the fastball anymore?’ I learned after being burned a couple of times!"

The Crabbers connection again kept Ellie’s career alive at a low point. He had wandered up to Winnipeg, a St. Louis affiliate in the Northern League, but then the Cardinals cut him loose in 1963. However, his closest friend with the Cangrejeros, pitcher William de Jesús, was playing with Jalisco of the Mexican League. De Jesús recommended Hendricks to Jalisco’s manager, major-league and Puerto Rico veteran "Jungle Jim" Rivera.3

From 1964 through 1967, Ellie put up very potent if not quite Ruthian numbers for the Charros, including 41-112-.316 his last year. He was also interpreter in mound conferences, as Rivera (whose Puerto Rican ancestry was dubious) could not speak Spanish!

It was playing every day in Mexico that caught the eye of Earl Weaver, who was managing Santurce. When Baltimore prospect Larry Haney got hurt, Hendricks also became a regular in Puerto Rico, and Weaver insisted that the Orioles should draft him in 1966. The Angels had a working agreement with Jalisco at that time, so they had Ellie’s rights. However, it took the extra endorsement of O’s scout "Trader Frank" Lane before the organization moved the following year. Hendricks finally made the majors in 1968.

"Hank Bauer was the manager at that time. And naturally anything that Earl brought to the table, he was against, because he knew Earl [then the first-base coach] was there to take his job! No matter what I did, I was wrong; he even changed my stance. Charlie Lau, who was our hitting coach, just closed his eyes. He said ‘Hank, I saw this kid hit in Puerto Rico that way, and he hit against major-league pitching.’ Earl was cringing, and he finally just said ‘I know you hate doing it, but just do it for me, please.’ By then I knew exactly what was going on, because I’d heard some stories." Earl’s epoch began halfway through the 1968 season.

Hendricks was a lesser but still vital cog in Weaver’s superb Orioles teams of 1969-71. He was the lefty-swinging half of a catching platoon with Andy Etchebarren, and his outstanding attribute as a player was handling the first-rate pitching staffs that were so crucial to the club’s success. In fact, John Thorn rated him the all-time best in this subtle skill in his book The Pitchers. The best examples may be how Hendricks was attuned to Jim Palmer, a cerebral power pitcher, and Mike Cuellar, a most crafty junkballer who had to outthink hitters after hurting his arm.

"They had a mental toughness. Palmer was probably the toughest of all to catch because he knew so much about the game. He knew himself, he knew every hitter, he knew every pitch that he threw. He knew what got hit and what didn’t get hit. Basically he was going to throw 85%-90% fastballs, you knew that as a catcher. But he would battle you the whole game, so that’s why he was tough to catch, because mentally you’d be exhausted when the game was over. But the days that he had great stuff, it was so easy."

Although Ellie’s arm was not regarded as very strong, it was highly accurate. He threw out 41% of opposing basestealers during his career.4 While Hendricks batted only .220 lifetime in the majors, never climbing above .250, he did have a good measure of home run power. All in all, he exemplified "The Oriole Way" of smarts, sound fundamentals, and a roster full of useful role players.

Throughout his time in the majors, Ellie consistently went back to Puerto Rico, which he always viewed as his secure place.5 His peak there was 1968-69, when he won the MVP award, and the following winter, Ellie and the Virgin Islands received a unique honor. On December 20, 1969, Santurce and Arecibo played a game in Lionel Roberts Stadium -- the only time a Puerto Rican league game has been held away from the Island.6 None other than Valmy Thomas made the arrangements.

Hendricks

has spent two stretches away from Baltimore, which he

regards as the low points of his career,

but even when he left the Orioles he paid dividends. In August 1972, he

was swapped to the Cubs for Tommy Davis in a waiver deal; Davis gave

the O’s three productive years as a DH, and they got Ellie back for

Francisco Estrada that October. Then in June 1976, Hendricks was part

of the big 10-player deal with the Yankees that brought Baltimore Scott

McGregor, Rick Dempsey, and Tippy Martínez. Under Billy Martin,

he

appeared in his fourth World Series but wound up accepting an

assignment to Triple-A Syracuse in 1977. Still, Hendricks thinks highly

of the other scrappy little bastard ex-second baseman for whom he

played.

Hendricks

has spent two stretches away from Baltimore, which he

regards as the low points of his career,

but even when he left the Orioles he paid dividends. In August 1972, he

was swapped to the Cubs for Tommy Davis in a waiver deal; Davis gave

the O’s three productive years as a DH, and they got Ellie back for

Francisco Estrada that October. Then in June 1976, Hendricks was part

of the big 10-player deal with the Yankees that brought Baltimore Scott

McGregor, Rick Dempsey, and Tippy Martínez. Under Billy Martin,

he

appeared in his fourth World Series but wound up accepting an

assignment to Triple-A Syracuse in 1977. Still, Hendricks thinks highly

of the other scrappy little bastard ex-second baseman for whom he

played.

"Billy was so much like Earl. Anyone that wanted to win, I wanted to play for, because you learn an awful lot. Even though I had been on successful teams in the minors, I didn’t know how to play until I got under Weaver’s tutelage. And then when I left Baltimore to come to New York, it was like looking at the same guy in the mirror. Billy wanted to win more than anything else. You sit and listen to them, they rant and rave, but you pick up an awful lot about the game."

"They hated each other’s guts, but they were so much alike, and I think that was one of the reasons." If anything, Ellie thinks Billy wanted to beat Earl even more because Earl had the upper hand more often. But he stresses how both were masters of roster management, player positioning, and all forms of in-game strategy. "Their teams were built around pitching and defense. That’s the one thing they did not tolerate, not being able to do the little things. Bunt the guy over, make the routine play, don’t beat yourself, let the other team beat themselves. That’s the way they played the game and that’s the way they managed the game."

In November 1977, "big-league daddy"7 Weaver rescued Hendricks again, giving him the bullpen spot that opened up when Cal Ripken Sr. took over for departing Billy Hunter as third-base coach. The winter of 1977-78 was also Ellie’s last with the Cangrejeros. He finished with a career total of 105 homers in Puerto Rico, third on the all-time list behind Bob Thurman and José Cruz, and he played on five league champions.

Ever since, Hendricks has been Baltimore’s most loyal lieutenant, enduring nine manager changes. He appeared in 13 games as a player-coach during 1978, including one as a pitcher during a 24-10 blowout. (See "The Night Elrod Pitched" in The National Pastime #16, 1996.) And when the rosters expanded in September 1979, he was activated for one last go behind the plate.

Like Horace Clarke, two of Ellie’s sons have played minor-league ball. Elrod Hendricks, Jr. (C/1B/OF) signed as a free agent with the Red Sox chain in 1983 and played one year before he got hurt and was passed over in favor of a bigger-money prospect. Maryland-born Ryan Hendricks (1B), a 38th round draft pick of the Orioles in 1994, rose to the AA level before finishing his career in 1997.

Ellie served two stints as interim manager in 1988 when Frank Robinson was laid up with a bad back. He posted a record of 4-11 with that woeful Orioles squad, the worst since the times of the St. Louis Browns. Many baseball observers are mystified that Hendricks has never gotten the job on a full-time basis, given his vast knowledge and exemplary people skills. His name was mentioned as early as 1983, Robinson recommended him as his successor, and the Orioles interviewed him as recently as 1994.

Inevitably, race entered the discussion -- it was a real factor, in Robinson's view, tied in with the usual Catch-22 of experience. In the '80s, Ellie sought a promotion to pitching coach, but the front office kept him where he was and he didn't make waves.8 His age (60) now also has a bearing. Still, Phil Regan, the O's choice after the ’94 season, was a first-time manager at 58. A better comparison would be the highly respected Felipe Alou, now 65.

Concerning the ambition to manage, he now says, "Years ago, I put that on the back burner. I no longer have the desire. There have been too many changes. There was a time when a manager managed the ballclub, took it into his own hands. It’s no longer that way. You have too many outside distractions. You have agents, GMs, owners, the players themselves." Of Alou, he notes "The patience I have, but you notice he’s got a young team. Once you get a veteran team, that goes out the window."

Hendricks is such a popular, fan-friendly institution in Baltimore that it is hard to imagine him ever leaving. He still warms up the pitchers in the bullpen, "as a matter of fact, the crouch releases some of the aches and pains," and he plans to continue coaching indefinitely.

"As long as they want me here, as long as I feel that I’m contributing, and as long as I still love the game. Because the love of the game is still there. Each and every day when I leave home, I think that we’re gonna win, and that’s the way I’ve always felt. When that stops, when it becomes a chore to come to the ballpark -- because I have not looked at it as work yet -- then it’ll be time to step aside."

Even more important to Ellie, though, is his community service. Named "Man of the Year" by various groups, he makes dozens of appearances a year on behalf of schools, charities, hospitals, and the like. He usually gets back to St. Thomas with the annual Orioles fan cruise. Truly a most amiable and altruistic fellow, Ellie more than amply repays what he regards as his great fortune in life. Baseball would not have to worry about image or fan relations if more people in the sport took a cue from Elrod Hendricks.

Notes:1. Bob Cairns, Pen Men (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 1993), p. 300.

2. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, p. 129.

3. Ibid.

4. Mike Klingaman, "For ‘Uncle Ellie,’ Another Family Reunion," The Baltimore Sun, April 1, 1998.

5. Jim Henneman, "Elrod’s Endless Appeal," The Baltimore Sun, November 7, 1994, p. C1.

6. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League, p. 48.

7. Henneman, op. cit.

8. Frank Robinson and Berry Stainback, Extra Innings, (New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 1988), pp. 2-3.

Born: December 22, 1940, Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas

Batted: Left Threw: Right

Height: 6’1" Weight: 175

Position: Catcher

|

Year |

Team |

League |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

1959 |

McCook |

Nebraska St. |

25 |

34 |

6 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

.235 |

13 |

4 |

1 |

|

1960 |

Wellsville |

NY-Penn |

73 |

217 |

36 |

51 |

8 |

1 |

11 |

36 |

.235 |

28 |

52 |

0 |

|

1960-61 |

Santurce Cangrejeros |

Puerto Rican |

23 |

36 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

.278 |

9 |

5 |

0 |

|

1961 |

DID NOT PLAY IN THE SUMMER |

|||||||||||||

|

1961-62 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

56 |

150 |

17 |

37 |

2 |

4 |

6 |

20 |

.247 |

21 |

31 |

2 |

|

1962 |

Winnipeg |

Northern |

69 |

213 |

25 |

45 |

7 |

2 |

3 |

22 |

.211 |

27 |

36 |

3 |

|

1962-63 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

36 |

101 |

11 |

24 |

4 |

0 |

4 |

12 |

.238 |

12 |

23 |

0 |

|

1963 |

Winnipeg |

Northern |

22 |

50 |

10 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

12 |

.280 |

8 |

6 |

2 |

|

1963-64 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

127 |

11 |

32 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

17 |

.252 |

11 |

33 |

0 |

|

|

Year |

Team |

League |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

1964 |

Jalisco Charros |

Mexican |

67 |

202 |

43 |

59 |

8 |

4 |

10 |

45 |

.292 |

48 |

38 |

3 |

|

1965 |

Jalisco |

Mexican |

128 |

411 |

100 |

117 |

14 |

8 |

35 |

98 |

.285 |

102 |

85 |

4 |

|

1965-66 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

65 |

199 |

19 |

37 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

18 |

.186 |

20 |

35 |

1 |

|

1966 |

Jalisco |

Mexican |

122 |

386 |

78 |

116 |

19 |

2 |

23 |

87 |

.301 |

107 |

55 |

6 |

|

El Paso |

Texas |

18 |

56 |

6 |

15 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

12 |

.268 |

7 |

14 |

0 |

|

|

1966-67 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

29 |

52 |

10 |

14 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

17 |

.269 |

6 |

5 |

0 |

|

1967 |

Jalisco |

Mexican |

131 |

434 |

124 |

137 |

18 |

4 |

41 |

112 |

.316 |

94 |

60 |

11 |

|

Seattle |

PCL |

13 |

36 |

3 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

.222 |

2 |

12 |

0 |

|

|

1967-68 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

61 |

197 |

40 |

50 |

6 |

4 |

12 |

24 |

.254 |

40 |

31 |

1 |

|

1968 |

Baltimore |

AL |

79 |

183 |

19 |

37 |

8 |

1 |

7 |

23 |

.202 |

19 |

51 |

0 |

|

1968-69 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

67 |

215 |

44 |

65 |

9 |

1 |

12 |

35 |

.302 |

26 |

27 |

1 |

|

1969 |

Baltimore |

AL |

105 |

295 |

36 |

72 |

5 |

0 |

12 |

38 |

.244 |

39 |

44 |

0 |

|

1969-70 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

60 |

194 |

31 |

49 |

3 |

1 |

10 |

35 |

.253 |

35 |

25 |

0 |

|

1970 |

Baltimore |

AL |

106 |

322 |

32 |

78 |

9 |

0 |

12 |

41 |

.242 |

33 |

44 |

1 |

|

1970-71 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

67 |

219 |

25 |

50 |

9 |

1 |

8 |

34 |

.228 |

42 |

29 |

1 |

|

Year |

Team |

League |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

1971 |

Baltimore |

AL |

101 |

316 |

33 |

79 |

14 |

1 |

9 |

42 |

.250 |

39 |

38 |

0 |

|

1972 |

Baltimore |

AL |

33 |

84 |

6 |

13 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

.155 |

12 |

19 |

0 |

|

Chicago Cubs |

NL |

17 |

43 |

7 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

.116 |

13 |

8 |

0 |

|

|

1972-73 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

58 |

170 |

31 |

45 |

7 |

2 |

12 |

38 |

.265 |

36 |

32 |

1 |

|

1973 |

Baltimore |

AL |

41 |

101 |

9 |

18 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

15 |

.178 |

10 |

22 |

0 |

|

1973-74 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

28 |

91 |

15 |

28 |

4 |

0 |

7 |

17 |

.308 |

18 |

13 |

0 |

|

1974 |

Baltimore |

AL |

66 |

159 |

18 |

33 |

8 |

2 |

3 |

8 |

.208 |

17 |

25 |

0 |

|

1974-75 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

59 |

187 |

27 |

43 |

9 |

0 |

4 |

22 |

.230 |

46 |

33 |

0 |

|

1975 |

Baltimore |

AL |

85 |

223 |

32 |

48 |

8 |

2 |

8 |

38 |

.215 |

34 |

40 |

0 |

|

1975-76 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

55 |

199 |

27 |

45 |

8 |

1 |

10 |

32 |

.226 |

42 |

37 |

2 |

|

1976 |

Baltimore |

AL |

28 |

79 |

2 |

11 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

.139 |

7 |

13 |

0 |

|

New York |

AL |

26 |

53 |

6 |

12 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

5 |

.226 |

3 |

10 |

0 |

|

|

Year |

Team |

League |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

1976-77 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

32 |

87 |

13 |

20 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

12 |

.230 |

18 |

15 |

0 |

|

1977 |

New York |

AL |

10 |

11 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

.273 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

|

Syracuse Chiefs |

International |

56 |

135 |

30 |

38 |

9 |

0 |

11 |

37 |

.281 |

21 |

16 |

0 |

|

|

1977-78 |

Santurce |

Puerto Rican |

34 |

92 |

12 |

21 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

11 |

.228 |

18 |

15 |

0 |

|

1978 |

Baltimore |

AL |

13 |

18 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

.333 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

1979 |

Baltimore |

AL |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

.000 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Totals |

Years |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

Major Leagues |

12 |

711 |

1888 |

205 |

415 |

66 |

7 |

62 |

230 |

.220 |

229 |

319 |

1 |

|

Puerto Rican League |

16 |

2316 |

343 |

570 |

78 |

19 |

105 |

349 |

.246 |

400 |

389 |

9 |

|

|

Mexican League |

4 |

448 |

1433 |

345 |

429 |

59 |

18 |

109 |

342 |

.299 |

351 |

238 |

24 |

|

Year |

Team |

League |

W |

L |

% |

Sv |

G |

GS |

CG |

IP |

H |

BB |

K |

ShO |

ERA |

|

1978 |

Baltimore |

AL |

0 |

0 |

.000 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2.1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0.00 |

|

Year |

Team |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

|

1969 |

Baltimore |

AL |

3 |

8 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

.250 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

1970 |

Baltimore |

AL |

1 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

.400 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

|

1971 |

Baltimore |

AL |

2 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

.500 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

1974 |

Baltimore |

AL |

3 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

.167 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

1976 |

New York |

AL |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1.000 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Totals |

5 Years |

10 |

24 |

6 |

8 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

.333 |

3 |

7 |

0 |

|

|

Year |

Team |

G |

AB |

R |

H |

2B |

3B |

HR |

RBI |

AVG |

BB |

K |

SB |

|

|

1969 |

Baltimore |

AL |

3 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

.100 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

1970 |

Baltimore |

AL |

3 |

11 |

1 |

4 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

.364 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

|

1971 |

Baltimore |

AL |

6 |

19 |

3 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

.263 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

1976 |

New York |

AL |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

.000 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Totals |

4 Years |

14 |

42 |

5 |

10 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

.238 |

5 |

5 |

0 |

|